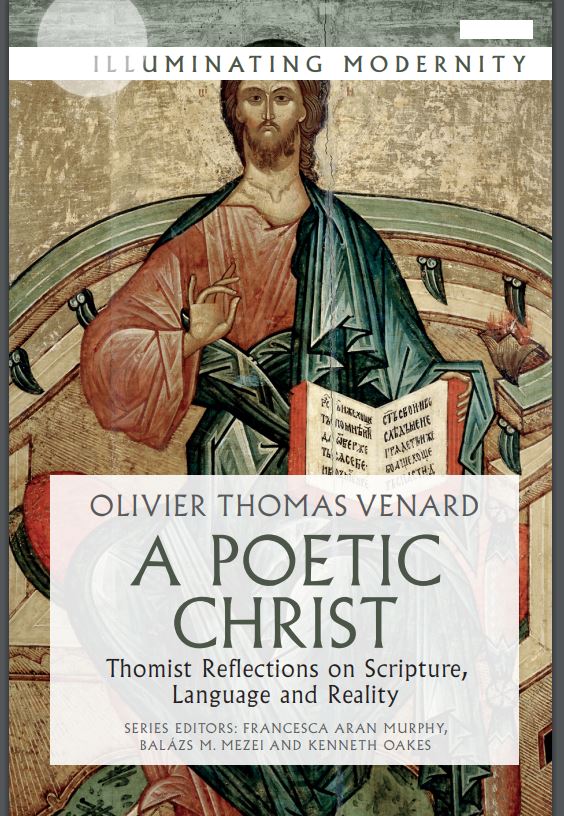

Early in April, a colloquium celebrated the publication of a book by our Executive Director, Olivier-Thomas Venard: A Poetic Christ: Thomist Reflections on Scripture, Language and Reality, adapted from his trilogy published in French between 2003 and 2009 (Littérature et théologie : une saison en enfer ; La langue de l’ineffable : essai sur le fondement théologique de la métaphysique ; and Pagina sacra : de l’Écriture sainte à l’écriture théologique), translated into English by Profs. Francesca Murphy and Kenneth Oakes, Notre Dame University.

For this colloquium, Prof. John Cavadini, director of the McGrath Institute, invited a dozen Christian and Jewish colleagues to reflect on the future of biblical studies, taking Venard’s work as an example of what it means to study the Bible scientifically as the Word of God, and as an invitation to rediscover the study of Scripture as a work of wisdom.

Artistic creation-according to Venard, essential to this rediscovery-was also on the agenda: the colloquium saw the world premiere of Latens Deitas, a piece for four instruments and two voices specially commissioned from Michel Petrossian.

- This was his second collaboration with La Bible en ses traditions (listen to his sublime interpretation of the confession of fire in G-Jeremiah 20:7-9).

Reconsidered as a sapiential discipline, biblical exegesis remains intimately connected to history and philology, but cannot be reduced to these disciplines. It must establish new relationships: with Jewish studies, literature, literary theory and linguistics, phenomenology and theology — not to mention the new partnership to be established with artistic creation as such, the only effective remedy for the “oblivion of language” once theorized by Hans-Georg Gadamer.

Under what (pre)conditions or presuppositions is such a project feasible? The dogmatic constitution of Vatican II Dei Verbum presents Scripture by affirming that God is its author, no less than the human authors who elaborated it book by book. Historical or literary “methods” will not suffice if biblical study is to take into account such an affirmation of divine authority. Not to take it into account, or to leave it to extrinsic hermeneutical or theological tricks, would mean ceasing to study it as the living Word.

Is there an untapped potential of Dei Verbum to reconnect Scripture, Word and Wisdom? If biblical studies are struggling to renew themselves in their present form, could a fine synthesis of history, contemporary philosophy of language, theology of culture, and traditional exegetical resources contribute to the renewal of biblical studies?