par Ombline, ENS Paris, AMI BEST 2019-2020

“It all starts with a Herculean task assigned to ants: inserting works of art inspired by the Bible. Which ones – all of them? Would we lack prudence (from which we insert many allegories, from the tarot deck of Charles VI to the temperas of Piero del Pollaiolo, in the Proverbs and the Sirach), or wisdom, we who accumulate portraits of Solomon? This may seem unreasonably ambitious, even proud. It is in fact very humble, because it requires taking one’s place, a very small place, in a project which, like the great cathedrals, will have thousands of small anonymous hands. Did we sit down first to see if we would have enough to go all the way? But who said that there was an end to the love of the Holy Scriptures? Love alone is not afraid of excess; and that’s good, because it is love that motivates this project. A mad, enthusiastic, unreasonable love of a Word that gives life and that cannot be put away in the cupboard – or on a dusty shelf in the library…

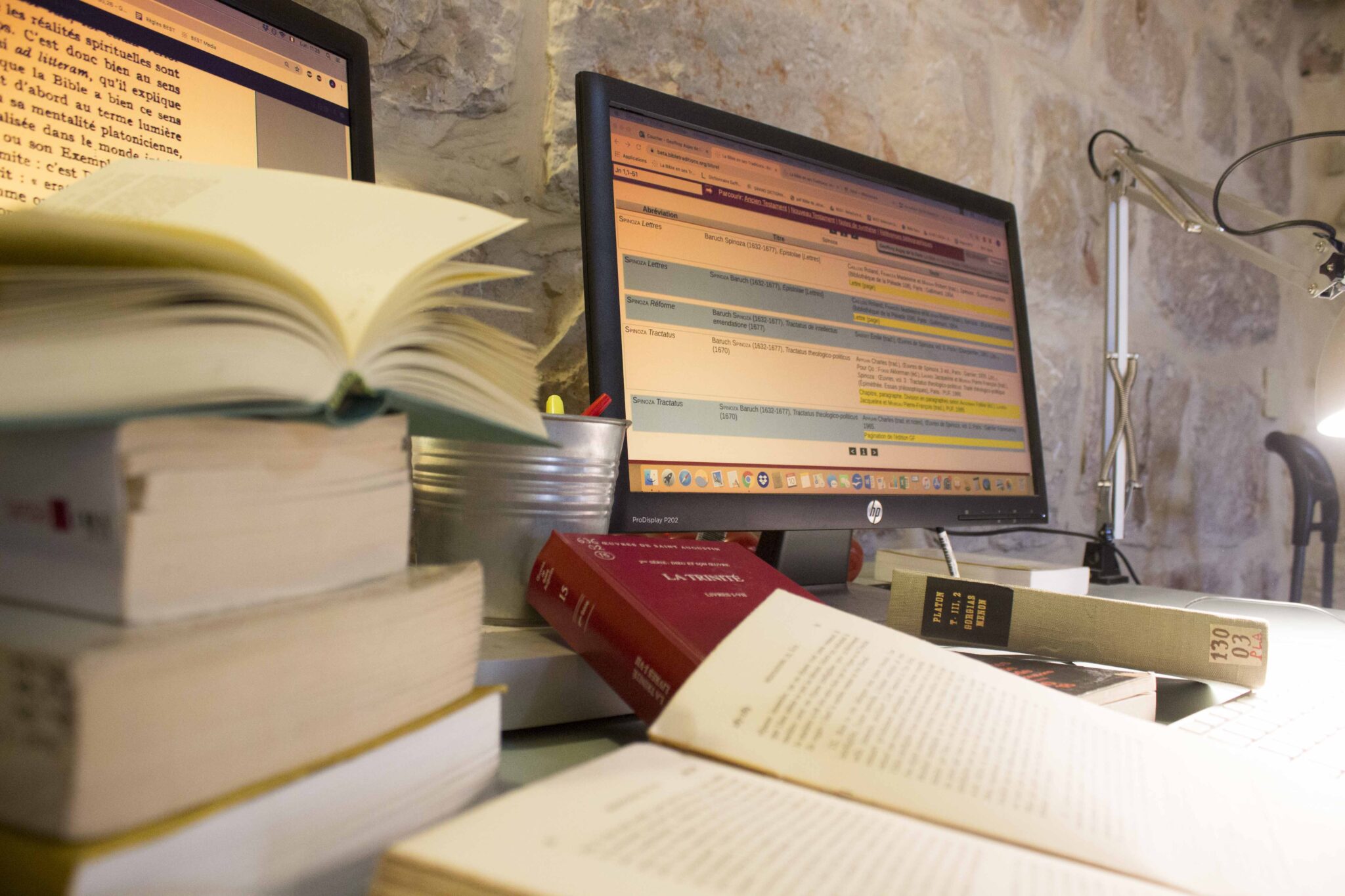

To bring in at least one image per chapter: that was the challenge launched a year ago – two years ago – by Father Olivier-Thomas Venard.

The researchers began by extracting a few stones from existing illustrated Bibles (Doré, Carolsfeld, the Bibles of the poor and the moralized Bibles…). The mosaic is gradually completed, and we see Moses through the eyes of Perugino and Poussin, Michelangelo and Chagall, Rembrandt and Ferdinand Bol, Jordaens and Tissot, Signorelli and José de Ribera. Monty Python rubs shoulders with Donatello: the project honours Dominican diversity. The Flemish and Italian primitives join the washes of François-Xavier de Boissoudy, and the contemporary installations the paintings of Rubens, Zurbarán and Veronese. This is an opportunity to discover or rediscover sometimes little-known masterpieces, to nourish one’s meditation on the mysteries of the rosary, and, by populating one’s Christian imagination, to Christianise one’s imagination.It is by humbly juxtaposing stones that one builds the edifice, which sometimes takes on disconcerting forms, and these are the most beautiful surprises. For the links appear, sometimes unexpected. So we learn that the Three Wise Men in a Russian cartoon come straight out of a twelfth-century Romanesque capital, that Desvallières goes to school with Titian, that Pontormo has Bill Viola as a pupil. Then everything speaks, everything responds, everything communicates: the lettering of a Book of Hours with the mantles of Van Eyck’s virgins, the red pages of Rossano’s gospel with Gauguin’s red-haired Jesus in his splendid agony, a new David whose flaming hair tears through the night.

God spoke once – twice I heard… and three times I answered.

God reveals himself in the Bible… and he wants to be answered! Scripture is a dialogue, and that is the whole point of the BEST project, which at last brings the history of reception into serious focus.

We discover the profane and biblical proverbs that pepper Brueghel, we silence our clichés about Jewish iconoclasm with the synagogue of Dura Europos, we follow Jonah to the toy department to find him emerging from the whale in a 14th century page, we see Lazarus in all his states thanks to Rembrandt’s engravings, Adam honoured by the angels in a Persian illumination. The book of Judges is read for the first time in its entirety and we think that Yael is not sung enough. Then we discover her among the Nine Preuses, and we notice once again that the medievals were wiser than we are. And since the BEST wants to be the new glossa ordinaria, we think we are in the right place.

Art historians enter the game

On March 3, 2020, during a meeting of a small group of art history professors from Lille, Paris 1, Nantes, Poitiers, Angers, at the home of our friend Professor Christian Heck, we established the formats of possible contributions in biblical iconography, from young researchers under the direction of their professors.

And already this autumn, the first promising notes reached us, on the Moses cycle…